EARTHA tackles one of the pressing issues of our time: our technological addiction to escapism. The title character discovers that when people immerse themselves in harsh stories in order to stay "connected" they are actually not truly connected at all. Without knowing their own thoughts they are unable to be with one another or even dream. Worse still, they cannot envision a future for themselves other than the bleak stuff fed to them by the powers-that-be. Eartha is the hero who helps people come back to their senses.

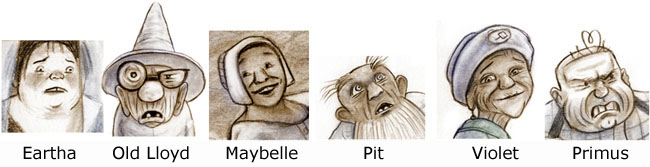

Some of the Characters of Eartha

Reviews of Eartha

©Matthew Laiosa

for Quietus.com

With only four books to date, Cathy Malkasian may not be the most prolific of creators, but she is certainly one of the most original. Percy Gloom, Wake Up, Percy Gloom, and Temperance all feature oddball realities that fall somewhere in between the minds of George Orwell and Dr. Seuss, and her newest, Eartha, is no exception. Perhaps the scariest thing about her latest work is how topical it is, considering that the book had to be created before Donald Trump was elected president. Science fiction used to take decades to prophesize societal shifts and technological breakthroughs such as the cell phone and iPad, but it seems that we now live in an age where if something can be imagined, then it will probably exist within the week.

Eartha tells the story of a gullible giant in a pastoral community of dwarves where dreams from a faraway city pop out of the ground to finish their narratives. Sadly, what once was a thriving valley filled with thousands of dreams a day is now visited by no more than a handful of dreams a week. Worried that something terrible has happened to the dreamers, Eartha journeys to the city and discovers a society where everyone is forced to stay awake in order to literally consume a non-stop supply of, I kid you not, fake news printed on biscuits evocative of President Trump’s twitter feed. Logically, the size of a biscuit limits the amount of information that can be distributed, so the ‘news’ is restricted to four word exclamations such as, “Hysterical jackass stabs recluse,” “Corn accident mauls has-been,” and “Fat jackass oozes calamity.” At one point in the story Eartha encounters the biscuit assembly line and amusingly asks a disgruntled janitor, “I see a lot of jackasses. Is the printer stuck?” And the janitor responds, “Of course not! The world is stuck!!” Which might be true since the people in control of this city is the Brotherhood of Bouncers, a clan of short balding males with the authority to grope any woman’s breasts of their choosing. Perhaps their slogan should be “Grab ‘em by the titties.”

Eartha is another frightening example of life imitating art, but the importance of storytelling is to remind us again and again that we can change. Unfortunately, change typically happens at a much slower rate outside of the world of fiction, but the more we expose ourselves and invest in quality storytellers like Malkasian, the faster real-world change can occur.

National Public Radio (npr.org), Arts & Life

Glen Weldon

April 11, 2017

Cathy Malkasian creates fantastic worlds out of her proprietary blend of melancholy and dream-logic, and peoples them with characters who are all too dully, achingly human. Her landscapes and cityscapes, rendered in gorgeous colored pencils, can seem as chilly and remote as her facial expressions seem warm and intimate.

In graphic novels like Temperance, about the lies that the citizens of a walled-off city tell themselves, and in her two Percy Gloom books, a gentle absurdism asserts itself so quietly that story elements like talking goats and heads that glow come off like prosaic details.

That's important, because without a sense of assured, implacable groundedness, Malkasian's narratives could easily feel labored, built as they are on such baroque, involuted infrastructure.

To wit: the opening pages of Eartha, Malkasian's latest, ask the reader to unpack a series of high-concept premises, any one of which could form the basis of its own book:

1. Eartha, "big as a boulder and softer than the moss that grew on it," lives in Echo Fjord, a bucolic land and whose citizens harvest dreams.

2. Said dreams belong to the residents of a faraway city.

3. The dreams that grow out of the ground are detained, and a thick paste called shadow applied to them, to keep them from floating away.

4. The dreams' minders touch the dreams to provide "a boost of energy to ignite them back into themselves."

5. The dreams then scamper through Echo Fjord toward a doorway, giving off brilliant rays of light out of the top of their heads.

6. As they pass through the doorway, they dissolve, having achieved their purpose.

That's... a lot to take in, granted, but Malkasian is so careful and considered in rendering the array of dreams (the sad, the joyous, the horny and the hateful) that we don't notice how much narrative work she's doing.

In the pages that follow, Eartha will depart her homeland to make her way to the nameless city, where she — and we — will meet the men and women who sent those dreams to her people across the vast sea. Unguessed-at connections among them will come to light; insights gained in those opening pages will aid Eartha in her quest (as will a talking cat, an intoxicating plum tree, and an old woman who knows more than she's letting on).

Such steel-trap plotting is something new from Malkasian, whose previous graphic novels have felt free to abandon familiar storytelling structure to double-down on some surreal image or theme. She's consistently shown an eagerness to walk the line between fabulist fiction and social satire, and Eartha is no different: the city's residents are addicted to biscuits printed with headlines of lurid tragedy ("Sinister Dandruff Muzzle Hen! Septic Jackass Gambles Naked! Prominent Orgy Provokes Rabies!"), and are ruled by thuggish, Mussolini-like figures who encourage the populace to embrace dull-eyed cynicism and performative despair.

Eartha will win the day, of course, because she maintains the ability to feel, and dream, and her sense of fairness will protect her from the city's corrupt politicians and its emotionally bankrupt fascination with the ugliness of life.

Eartha is an extended dream with a fixed moral compass, a story about the central and transformative power of believing in humanity, even when — especially when — it lets you down.

The Comics Journal

Frank Young

June 29, 2018

Cathy Malkasian began her career in animation in the early 1990s. If you have kids, or like TV animation, you’ve probably seen some of her episodes of Curious George and The Wild Thornberrys. She turned her creative attention to graphic novels in the mid-2000s. Her first book, Percy Gloom (2007), earned her an Eisner Award nomination and its Most Promising Newcomer Award.

Eartha is Malkasian’s fourth graphic novel. It, too, has been nominated for an Eisner Award, and garnered critical acclaim. On the surface, it looks like a Tolkienesque fantasy, with all the tropes that genre suggests. It is such a fantasy, but it uses its potentially groan-inducing trappings to tell a layered, metaphorical story that seems just right for the America of today.

The world of Eartha is reminiscent of Percy Gloom, with its winding cobblestone streets, byzantine alleyways, and rich foliage. The books share a vision of blundering, over-complex, and comical bureaucracy. The reader is aware that they’re in a thought-out, obsessed-over world—one that suggests other artists, from Fred Opper to Maurice Sendak, but doesn’t seem derivative of those works.

Malkasian’s subdued color palettes, careful graphite renderings and versatility of unusual body language and facial expressions are impressive throughout Eartha, which takes its time to set up its story and introduce its characters.

The book’s two major themes—the split between rural and urban living and the insistent presence of social media—keep Eartha from being another Joseph Campbell-cliché Hero(ine)’s Quest for Something, as this type of fantasy story too often succumbs. A gentle, sometimes dark humor further leavens the message. Its metaphors aren’t delivered with a solemn face; nor is a moral preached. Right and wrong in Eartha are matter-of-fact; sometimes the latter is underlined more than necessary, but the artist’s delight in the human comedy wins out.

Eartha begins in the rural Echo Fjord, a humble agrarian utopia whose residents till the fields and, in better times, harvest the dreams of the far-off City across the Sea. Eartha, described in the book as “big as a boulder and softer than the moss that grew on it,” towers over the other Fjorders and is friend to all.

The dreams manifest themselves as glowing lights in the ground which sprout to reveal the dreamer’s self-image, as they enact their subconscious drama out in the wild. These internal dramas and comedies reveal potentially embarrassing and shaming things about their dreamers. For generations, the Fjord people have welcomed these emissions and watched their brief psychodramas before they fizzle away.

The dreams give the Fjord people a sense of the larger world. Their sudden abatement sends the community into a funk. Eartha witnesses a monumental dream of a city child’s in which the moon falls from the sky and seems to land in the fields of the Fjord.

This dream causes her to be sent to The City, under laughably false pretenses she is too naïve to detect, by Old Lloyd, the irascible archivist of the city-generated dreams. He has a bigger reason for dispatching Eartha to The City—he wants to find out why the dreams, which were once innumerable, have dwindled down to a drizzle.

I know… it sounds hokey. As a dedicated non-fan of the fantasy genre, I was a tough sell for this book. Malkasian’s stories have clichés as their foundations. How she wriggles through them and twists them around (and inside-out) is what makes Eartha compelling.

Eartha was created just before a certain unrestrained egomaniac gained control of the White House. Malkasian must have sensed something in the air. Her charismatic, volatile City leader, Primus, shares some off-putting and abrasive behaviors with You-Know-Who, but is not a caricature or satire of You-Know-Who. He embodies the pettiness and self-importance of the unchecked male ego—strutting and preening, absurd in a tiara and checkered sports jacket, seemingly sure of himself as he struggles with his confused libido and sublimates it through acts of greed and violence.

Primus has hooked the City’s residents on buttery pieces of shortbread stamped with random ennui-causing phrases (FAT JACKASS OOZES CALAMITY, reads one biscuit). These fattening crumbles of blank verse have the urban dwellers in hysteria. Due to this citywide focus on the cookies and their depressing messages—to which the residents are addicted—their dreams have almost ceased to be. A metaphor for Facebook, perhaps, or for the compulsive way we ingest social media, which confronts us daily with the ugliness of the world, alongside adorable cat videos and the occasional grain of good news.

Malkasian’s love of eccentricity steers this story. Despite the narrative clichés—country vs. city, fish out of water, the evil empire that must be toppled—Eartha surprises the reader with its loving deviations from the genre ticker-tape. Malkasian enjoys building scenes around cranky, self-absorbed characters. Virtuous or villainous, Eartha’s cast relishes their opportunities to vent their spleens, ramble about the events of the past or pass time with chit-chat. The rantings of Old Lloyd, the archivist, are delightful. Malkasian has a fine ear for dialogue; her characters rarely utter the mundane.

Eartha’s graphics support its narrative with grace. Malkasian’s style evokes children’s books and (no surprise) animation. Her skill with the human figure—which she deftly caricatures and endows with fleshy presence—is a delight to encounter. She distorts these figures in a manner that recalls early 20th century American newspaper cartooning, although animation’s squash and stretch principles are a more likely source. Her modeled monochrome figures, often up-lit for a theatrical gaslit effect, are commanding and convincing. Much of the book’s success is via its solid, expressive artwork and its control of color and its absence.

Much of Eartha resembles a tinted silent film, with rich sepias and hints of slate blue and subdued green. Restrained pastel blue and violet enters the story as needed, to highlight changes of venue and mood. So thorough is this palette that the absence of traditional bright colors isn’t noticed—or needed.

The elision of strong color is broken by three full-page section headers that show Malkasian’s skill with vivid pastels. They’re startling interludes amidst the earth-tones that dominate the book. It’s impressive to see how much the artist can achieve without a broad palette of colors.

Eartha is the rare fantasy story that can be read without the sense that you’re about to be taxed by endless clichés. Like the animated features of Hayao Miyazaki, it offers elements of escapism without the escape. It offers a timely reminder for us not to get side-tracked by the hysteria around us, or to pretend that we can wish away offensive behavior and aggressive personalities. At its best, Malkasian’s Eartha collides genre tropes and painful truths in a charming, thoughtful and sometimes edgy entertainment.

The Globe and Mail

April 13, 2017

Watching Cathy Malkasian construct a world is a pleasant and gently surprising experience. The visual splendour and quizzical customs she dreams up to outfit the stomping grounds of Eartha, a genial giant who's embarked on a quest, share much of the verve of Pixar's weirder ideas, along with some of the darkness of Don Bluth's cartoons (the book's scenes of murder and self-abuse make this more of a PG-13 affair). An award-winning animator herself, Malkasian briskly sweeps her story along, from the introduction of Eartha's idyllic homeland, Echo Fjord, where the country folk harvest dreams out of their soil like crops, to our heroine's journey to the Orwellian City Across the Sea, where she must find out why the city folk have stopped dreaming. The allegory here can be a bit pat – "Without dreams," Eartha protests, "we are lost," as the citizens around her rather devote themselves to something much like the Internet – and the charmingly strange notions can arrive at such a clip that they just start to pile up, but Malkasian's dexterous, droll and velvety drawing smooths over many such bumps.

Comicsverse

Murphy Wales

April 15, 2017

One of the biggest controversies of the year has been “fake” news. From CNN, to Fox News, to independent websites, many are questioning whether news sources are truly reliable. This is because there have been instances of information being omitted, unchecked, or falsified, creating a false narrative. This is particularly alarming because there are those out there who have no qualms spreading a lie and have no regard of its repercussions. Because of this, the public has been split, questioning who’s trustworthy and who’s not. Things have become rather complicated this year, and EARTHA explores the problem of news and reminds readers how to trust again.

Written and drawn by Cathy Malkasian, EARTHA is a story set in a fairytale world where a number of bizarre things run about, like talking animals and physically-manifested dreams. Despite all these oddities, it still hits home with a message highlighting the significance of empathy and honesty. The story follows a girl named Eartha, who lives in the land of Echo Fjord, where residents were once accustomed to being visited by the dreams of city folk from across the sea. However, it seems that the dreams have become scarce. Fearful of what may have happened to the city, Eartha ventures off to figure out what is afoot and finds that the citizens have fallen victim to biscuits with small messages from the outside world on them. With nothing but compassion, Eartha must free everyone from the biscuits’ grip and bring back the dreams.

From the get-go, the comic expresses how society can be obsessed with news. This is evident when Eartha reaches the city and finds that the people are disassociated from one another, focused exclusively on their biscuits. When she approaches them or questions their pastry, she is quickly labeled a threat or a liar. This, of course, is a comparison to how many pick and choose who to listen to and how impractical news sources can be. It seems fanatical that one would take the word of a biscuit over a person, but considering the odd sources people will trust these days, is there much of a difference? But let it be said that the comic does not patronize the biscuit-eaters. Instead, it portrays them as people who want to be aware of the world around them and want to be critical. It shows that it’s not uncommon for people to want to be enlightened. A character named Betty, a talking cat, best expresses this desire, “Nobody sleeps! Afraid they’ll miss out. They don’t travel outside the city, afraid of missing their news from outside the city. They want to be here, yet they’d rather be anywhere but here!” So no one is necessarily wrong for trusting the biscuits, but wrong for losing trust in one another, and more importantly, wrong for not being critical of those who give the news.

Along with its metaphorical prowess, EARTHA proves to be a fun read because of how well the dialogue is written. The conversations between characters will flow naturally, using pedestrian diction, while expressing complex thoughts that challenge you. Some characters will feel familiar, Old Lloyd for example, a crotchety old man with a silver tongue, while feeling unique in their own way. I myself felt as though some characters were from my family arguing and laughing over something mundane. It has a very human quality to it; it feels very natural.

Another reason I’m so avid for people to read EARTHA is that it has such a unique style. Malkasian’s art is easy to visually digest, as seen in her other works — such as TEMPERANCE and PERCY GLOOM — and is easy to engage with. Her landscapes are soft to the eye and seem ever-expanding; the soft color palette is smooth and seems akin to the work of Georges Seurat. Even scenes that show ample space between the foreground and background have certain characters or elements detailed explicitly to draw your focus to them. There’s always something intriguing on the page; it’s a talent that’s seldom seen and deserves recognition.

In addition, Malkasian’s character designs are impeccably inclusive. There’s a body type for every shape and size, showing that Malkasian isn’t afraid to portray the human form in all its variations. Every one of them looks so animated and vibrant, and she achieves this without making certain features hyperbolic. It shows an honest depiction of people that some aren’t favorable of. People are old, large, and not always attractive. It’s this honesty that reminds me that people are fragile and have basic desires. This shows when Malkasian reveals the dreams that manifest. Each one is personal, giving way to secrets, memories, and goals. It shows the unbridled ego, with all its flaws, that we all have and that it’s better to confront them, rather than cast them aside. As a whole, EARTHA is a fantastic spectacle from this year that I wholeheartedly suggest anyone read. It’s culturally relevant, enchanting, and fun.

The Duquesne Duke

Nicole Prieto

April, 2017

Through masterful pencil lines and emotive scenery, Cathy Malkasian’s “Eartha” tackles difficult subjects about society and politics through a strange world where dreams take corporeal form. “Eartha” is Malkasian’s fourth graphic novel and follows the misadventures of the book’s namesake as she works to solve a bizarre mystery. Echo Fjord is a pastoral farming area cut off from the world’s problems. As its kindest resident, Eartha uses her large size and great strength to help its many denizens with their troubles or chores.

Aside from their peaceful life of growing and producing, one of the Fjord folk’s most important tasks is to shepherd City people’s dreams. Dreams have always emerged upon Fjord shores and fields to play out their distant owners’ fantasies. For 1,000 years, the Fjord folk have been more than happy to guide them to completion, even long after the City’s location became lost to time. Trouble arrives, however, when the dreams suddenly stop coming — but then return with an array of ominous visions. Something is wrong, and Eartha is unwittingly tasked to find the City and discover the source of its problems.

As in her 2010 graphic novel “Temperance,” Malkasian’s soaring cityscapes, maze-like arcades and horizonless fields display her remarkable, genre-defying imagination. The book is drenched in soft violets and sepia tones that invite warmth and create beautiful contrasts. Readers will find themselves caught up in fantastic illustrations that perhaps evoke the kind of “backwards nostalgia” that some characters in “Eartha” are afflicted by.

As a story, the book is layered with symbols and messages that make simple interpretations as unrealistic as the book’s abstract universe. On one hand, Malkasian contrasts busy city life with rural steadfastness. But on the other, she refuses to state that Fjord folk are superior to City people. The Fjord folk fully embrace the wild dreams from their distant counterparts, commenting on their virtues and beauty, no matter how simple or sordid they may be.

This is an interesting narrative move that subtly encourages readers to forgo stereotypes about different ways of life. Though City life at first appears cruel to Eartha, she meets with different people who display the same caring attitudes and rich personal histories as the Fjord folk.

Malkasian also fits in unsubtle criticism of social media and performative grief, doing so almost entirely without invoking them by name. For example, Eartha finds herself in an alien world that might be uncomfortably familiar to readers. She learns that an army of plaid-wearing gangsters is exploiting the City people into trading valuables for boxes of biscuits printed with dubious headlines. The City people, obsessed with “Biscuit News,” become paralyzed with terror and addicted to comfort-eating the very pastries causing their distress.

While perhaps ribbing on attention-grabbing headlines and fake news, Malkasian avoids descending into uncritical generalizations about the news industry. Instead, she warns against the desire to appear worldly through exaggerated displays of grief. Through her character Eartha, she emphasizes how action and compassion are far more productive ways to handle problems, and as in “Temperance,” love and the desire to connect ultimately win the day.

As a storyteller, Malkasian is unafraid of difficult subjects and fully embraces the complexity of human nature. Eartha is a likeable and caring heroine, but she is not a faultless archetype. When Eartha is at her worst, Malkasian lets her say or do things she would otherwise regret, such as threatening harm to another. Malkasian understands that people are complicated, and even the most well-meaning and loving among us have moments of abject selfishness or cruelty.

Still, even though Malkasian’s abilities as an artist are on full display, the style of her narrative is somewhat less impressive. Compared to “Temperance” — which made effective use of subtle foreshadowing in its first pages — “Eartha” tends to introduce significant plot points or characters only when they become significant to the story. This is arguably a deliberate move by Malkasian; it does makes the reading experience more fluid and dreamlike, though it comes at the cost of a more cohesive plot.

At 255 pages and packed with dense subjects, “Eartha” is not something to be tackled in under an hour. It is a remarkable new release with relevant messages for a modern audience. Take some time to sit back and enjoy it — and do not feel too bad if a lot of it goes over your head the first time around.

Megan Purdy

for The MNT

In Echo Fjord they capture and document dreams. This rural village has an economy typical for isolated towns, they fish and farm and craft, but their local culture is entirely built around experiencing the dreams of others. Residents are happy to drop their daily chores in favor of chasing down stray dreams, drawing shadows on them with buckets of soot, learning their secrets and then setting them free to dissipate. It’s a slow and sleepy town populated by slow and sleepy characters common to such pastorals, sweet hearted farmers, sly old men who have tricks up their sleeves but no malice, and hard working folk who’d love a drink or three at the pub, thanks for asking. But it exists in a mildly fantastic other-space, one with an oblong sun and moon, dreams that cross oceans like waves of light and sound, talking animals, and twists of luck and minor destiny.

Malkasian illustrates this in snowy blues and warm, sepia browns, all soft pencil crayons curls and shadows. Echo Fjord is an idealized small town, governed by unusual rules to be sure, but a one with a wholesome, bucolic lifestyle – the Residents live in harmony with nature, supernature and each other. They are tolerant of each other’s quirks, generally hardworking, broadminded and wholly fulfilled – that is, until the city’s dreams stop coming.

Eartha opens with Echo Fjord suffering from a sudden slowdown in dreams. The residents are puzzled by the change in their routine, but more than that, they are struggling with how it changes their sense of the world and of their own identities. A truly isolated village, having had no contact with the outside world for 1000 years, Echo Fjord depends on those roving dreams to draw boundaries between what the Fjord is like and what the City is like; what they are like and what City folk are like; what their world is and their place in it. These dreams are the source of their entertainment and their philosophy – their experience of them, documentation of them in the Fjord’s great dream archives, and their retellings – is the basis of their local culture. What is Echo Fjord without the echos of this other place’s stories? These other people’s lives? It’s not that they live hollow lives – the shepherding of dreams brings them great fulfillment and insight – but this sudden lack of dreams does leave them bereft. The purpose of their lives left interrupted.

Naturally, someone must be dispatched to discover the source of this trouble, but because the Fjord has been isolated so long, no one quite knows what to do about it. No one but the town’s crabby old dream archivist, who tricks the book’s eponymous heroine into investigating. Eartha, convinced by Old Lloyd that he needs “smoke sticks” (cigarettes) to live, sets off for the City to bring back a supply of his medicine. Upon arrival she is almost immediately embroiled in the local political turmoil which has interrupted Echo Fjord’s supply of dreams.

The trouble is that people have stopped dreaming altogether, convinced by a band of piratical capitalists that they should live for one strange product – biscuits with snippets of international news printed on them. The leader of these biscuit bandits, Primus, has gangs of alike dressed “bouncers” not-so-gently encouraging biscuit doubters to get back into the daily biscuit grind. The bouncers use force when necessary to keep up the demand for biscuits, but they, like Primus, delight in it too. This is a gang of capitalist bullies, clinging to a credo (and product) that makes no sense, but in reality, driven by greed and meanness. Primus, a grinning, opportunistic authoritarian means to seize control of the City in the wake of the sudden death of Mr. Biscuit, the original news biscuit baron, causing a crisis in the biscuit exchange so that he can better exploit the moment.

Eartha, new to the city and very much ignorant of its politics, knows she must somehow help the City through this crisis in order to give purpose back to Echo Fjord. On meeting her, Primus declares her to be a giant “She Bumpkin,” who exudes a strange sense of stillness which disturbs him. She isn’t interested in frantically consuming biscuit news or engaging in violent power plays. And while she, like Mr. Deeds or any other country folk gone to the big city, is often easily mislead by more sophisticated and cruel city folk, she is far from ignorant about human nature, or indeed about the culture of the city – she’s been watching their dreams her whole life, after all. Primus doesn’t know what to make of her and his response is violent, as is that of all of the other minor villains in the book. Echo Fjord’s whole culture is based on loving, nurturing, and sharing the experience of dreams. Their lifestyle balances the tangible immediacy of rural living with deep love of stories and storytelling, valuing above all, the capability to dream.

This is all, as you are probably suspecting, political allegory. Echo Fjord’s dependence on outside dreams isn’t so great but its sheer love for them is laudable. The City’s recent obsession with biscuit news, which is making them fat and tired and miserable, is fueled both by curiosity and self-destructive impulses. Learning is good and political engagement is essential, but obsessing over staying up to date and being the most engaged, the most affected by all this terrible news, is not.

The City is affected by a malaise stemming from what all readers will immediately recognize as a combination of information overload, performative media consumption, and rampant fake news. Its residents can no longer dream because they are overwhelmed by the biscuit market, which forces terrible news on them and then comforts them with delicious pastry. Consumption of biscuits, and particularly public consumption, has quickly become the only relevant currency. Primus and his band of thugs, who model themselves after Mr. Biscuit – himself a fictionalized version of the real man behind the news bakery – have built whole lives around his late life angry mutterings. See, the whole thing is a misunderstanding built on a sham, but Primus’ control of the populace is real. In him it’s easy to see any number of populist or authoritarian hucksters. His vicious grin, his sexual obsessions, the absolute emptiness of his political philosophy and his absolute willingness to commit to any violence, necessary or pleasure – these are all so reminiscent of Trump and Pence and their clown car of fascists.

In Echo Fjord we have a small isolated town that loves its traditional way of life and doesn’t look forward to big changes. Yet, it is also a town that has love for the outside world and certainly doesn’t fear it – Eartha’s journey to the City gets the Fjord back in the business of shepherding dreams, but I wonder if the town wouldn’t be served by some form of renewed contact with the City. Their philosophy holds that it’s unethical to have too much contact with people whose dreams they have intimate knowledge of, which is why they broke off contact with the City in the first place, all those years ago. Eartha does have a certain advantage over certain City residents, who she has encountered before in their dreams. But it seems as though Echo Fjord is so busy shepherding the dreams of the City that it does not always take time to dream, and grow, for itself.

One of Eartha’s great strengths is that it creates a definitive sense of place, without relying overmuch on one specific historical milieu, and one that is naturally diverse. This is not a white fantasy world – residents of both Echo Fjord and the City are diverse and ethnic tensions are not a driving force for their current cultural troubles (though there’s some suggestion they may have played a role in the decades past War, which was the catalyst for the whole biscuit news thing). Eartha’s mother and “best friend” Maybelle are black women, as is a crucial character introduced in the book’s third act. That “best friend” gets scare quotes because I find it hard to read Eartha and Maybelle, who embrace (and maybe kiss?) several times as friends and not girlfriends — but I’m not sure of Malkasian’s intent with them. It’s not that Malkasian insists they are friends, not lovers, or that the book is in anyway homophobic, but more that I’m uncertain. Malkasian imbues Eartha with a tone somewhere between a modern fable and a traveller’s tale, like Gulliver’s Travels with less edge, and while this contributes much to its charms, it also does not lend to close examination of the little details of the book. That which isn’t relevant to the main plot is not much explored. We never do learn much about Eartha’s family or her friends in the Fjord.

Malkasian’s landscapes and architecture are done with a soft touch and round edges, but enough detail and texture to give both Echo Fjord and the City depth and texture and character. The whole of the book is done in shades of blue and brown and occasionally green. While dreams and sea storms are illustrated with the darkest blue in Malkasian’s pallette, she doesn’t use colour to indicate things like character or morals – she relies far more on body language and expression for that. Likewise, while some of the book’s most harrowing scenes take place in the narrow, dark spaces of factories or back alleys, others take place on farms. The City’s architecture isn’t solely one of cold capitalism and enclosure and Echo Fjord’s bucolic idyll is interrupted by the odd technological contraption. They are both characters, like well drawn fictional places can be, but neither of them are simple, purely good or bad.

While I was immediately charmed by Eartha’s pastoral come political satire, its main character made me a little nervous. She’s tall and fat, gap toothed with lank hair and plain clothes. Her occupation in Echo Fjord is carrying things and animals and people – because she is so much bigger than the residents of Echo Fjord – and she’s known for being a bit gullible. Her character design combined with the book’s plot had me wondering for a long time if she was meant to be a salt-of-the-earth savant, a kind of agglomeration of stereotypes around fatness and intelligence – the sort of sweet fool that more cynical characters are meant to learn from and emulate. It wasn’t until about halfway through that I became entirely comfortable with Eartha, and certain that she wasn’t meant to occupy this space in the story, even as her design sometimes invoked those harmful tropes.

Eartha certainly is your typical fat but strong heroine, not pretty, but strong in body and morals alike. She is also clever, with a deep understanding of character and ethics, though is indeed gullible to an astounding degree. And while she is every bit the country mouse to a cast of more worldly city mice, she is not an object lesson. She does not come to the City to serve as a moral benchmark against which dissipated sophisticates should measure and improve themselves. Her strength is her compassion, not “innocence.”

Eartha is a beautiful book. Entirely hand drawn and hand lettered by Cathy Malkasian with, it feels, like endless care. Its combination of gentleness and fierce social and political commentary makes it a surprisingly affecting read — it got to me the way Pixar movies can surprise you with an emotional gut punch (thinking of you, UP). It also gives it distance, making the book both timely and timeless. Despite its clear relevance to our contemporary political climate, it also works as a more general fable about cultural values, the social role of both news and fiction, and the importance of valuing your dreams and those of others.