July 23, 2010

©Newsarama.com/comics

By Michael C. Lorah

posted: 16 June 2010 10:06 am ET

Comics and graphic novels, we’re told, can do anything, yet few offer the type of challenging cultural and societal commentary that asks for – no, actually demands – repeat reading.

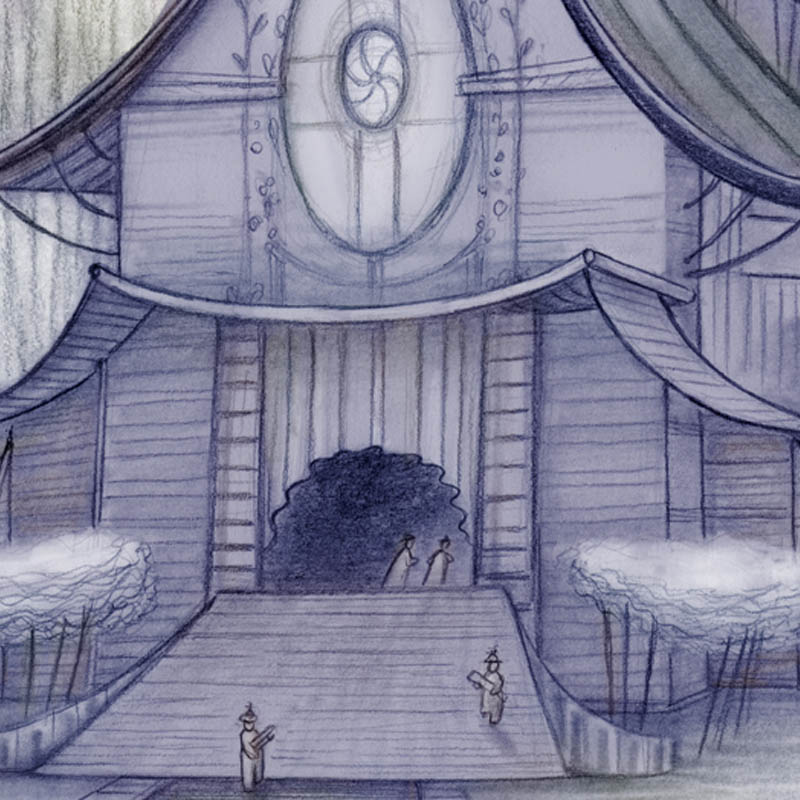

In her second graphic novel, following 2007’s Percy Gloom, Cathy Malkasian expects readers to revisit the world she’s created and to ask themselves some very hard questions afterward. Temperance, her new book from Fantagraphics, doesn’t provide answers; it only forces the questions, examining the role of violence and control in modern society.

Minerva, Temperance’s most central character, finds herself torn between the influences of angry, mistrustful Pa and beautiful, serene Peggy, and when she takes charge of a cloistered society aboard an enormous ship, Minerva’s looks for the most powerful means of keeping her flock focused and content.

The title character Temperance, a wooden doll carved from a forest where Pa and Peggy lived, has witnessed the range of humanity, observes the antics of humanity until he feels compelled to act, despite being himself torn apart by the conflicting influences of Pa and Peggy.

We spoke to Cathy Malkasian about working on the book and creating a narrative as nuanced and open to personal reactions as Temperance.

“Temperance started percolating years back,” she explained. “Originally it was going to be a graphic novel, but it thumbnailed out at 550 pages, and I just couldn’t commit myself to something so intense for so long. Then I wrote it out as a draft for a novel, but that proved unsatisfying, since so much of my writing is visually descriptive. Both of these earlier versions had very different plots. This version took two years to do, and was a thorough overhaul of previous versions. Many characters were cut out, and the plot changed drastically.”

Malkasian laughed at the notion of readers trying to pull all the meaning from Temperance in one sitting.

“I don’t expect people to absorb all of this in one go. I’m always a bit bereft after reading a story whose meaning drops off with the final page! What I like most about books is that they can be re-read as many times as needed,” she said. “I want this story to provide something new to readers each time they visit. The ‘graphic novel’ format seemed to be the best means to tell this story. But implied in your question is the view that comics aren’t as ambitious as written works. Is this true? And what about the reading experience? When we open a comic, as opposed to a written novel, are we giving our experience comparable respect? Writing an extended comic is just as demanding as writing a novel. You go through all the same rigors of research, structuring, character development, drafts, etc., except that with a comic you’re working in two very different languages at once.

“I had no particular literary goals,” Malkasian said, before admitting, “What I wanted to touch upon was our current state of engaging in distant wars and how these have altered the lives of returning soldiers and their loved ones. This and the increasing taste for violence in our cultural palette. Do these currents rise together? Is the latter a reaction to the former? I still don’t know, but I have a feeling we’re seriously rearranging the role of violence in our collective mind. As usual, we are flirting a lot with violence in our popular media, in a very child-like way. We treat it with a kind of graphic fascination, but are still unnerved at exploring its consequences. Unless you show the full story you’ll never get past the flirtation stage. So I wanted to make a story all about the long-term consequences of destructive choices.”

On the subject of the book’s four primary characters, Malkasian explained, “Pa is an embodiment of the natural force of entropy and all its expressions. He also embodies the human fascination with and revulsion toward this force.”

He is contrasted by Minerva, who is driven by both her love for and fear of Pa. She manages to create a fairly productive, if deluded, society by promoting Pa as a figure of mythic proportion and providing a healthy bit of paranoid fear-mongering.

From her own perspective, Malkasian says that “Minerva is simply trying to manage in a world shaped in large part by Pa. She starts out believing that, by staying close to him, she’ll be near the source of power and stay out of harm’s way. It’s a crazy logic, but one that people often employ when living in violent cultures with no way out.

“Paradoxically she uses the worship of Pa to shield herself from him, surrounding herself with a community what worships him, reinforcing in them the delusions she once held. In this way she is never alone, even though she is probably the loneliest character in the story.”

Continuing on to discuss Peggy and Temperance, she said, “Peggy is actually the inextricable foil of Pa, the force of creation and the persistence of memory. Her influence seems to be in short supply, but it’s there, as a whisper to Pa’s shout. That’s sort of the state of things in our world, too. The doll, like everyone and everything, contains both forces. It can get pretty hot headed with anger, with those destructive urges! Not the best disposition for a piece of wood.”

The word temperance typically refers to a movement against alcohol or a general moderation of “excess.” Temperance manages to avoid the extremes of both Pa and Minerva, yet there’s a clear rage in him as well.

Discussing Temperance’s motivations, Malkasian offered, “The word also has its roots in a balancing of forces. The doll is trying to understand the human world and how it processes and balances natural forces in the form of emotions and ethics. It also has a timeless, enduring quality – a piece of wood that has taken many, many forms and somehow retains its awareness.”

Coming from a background in animation, Malkasian – who co-directed 2002’s The Wild Thornberrys Movie feature film – began pursuing comics as a creative outlet several years ago. The experience served as a training ground for her, but also served to push Malkasian toward the type of challenging stories she wished to see in animation.

Malkasian: “I have learned and yearned from being in animation. Technically it’s been my art school. But in terms of stories it’s left me wanting. I think that our friends in Europe, Canada and Russia have more freedom to tell a greater range of stories through animation. Hopefully we’ll get there, too. I love animation and really look forward to the day when the content matches the sophistication of the medium.”

With Temperance in the bag, Malkasian’s already moving forward with new comic book projects. Next, she says, is “a comedy, which will be a nice change of pace!”

©fantagraphics.com:

Diaflogue: Cathy Malkasian exclusive Q&A

We're very pleased to present this interview with Cathy Malkasian conducted by contributing Mome cartoonist Robert Goodin. We typically have Fantagraphics staff members conduct these "Diaflogue" interviews, but when assigning an interviewer to talk to Cathy, I couldn't think of anyone better than Rob, who has known Cathy for years and published her first minicomics under his Robot Publishing banner. I was thrilled when Rob and Cathy agreed to have this conversation.

Robert Goodin: I think you had a bit of an unusual path to comics. Why don't you tell us about your background like education and your main profession.

Cathy Malkasian: The wonder of mixing words with pictures started in kindergarten. We were given the task of doing little booklets depicting some event in our lives. We drew the pictures and the teacher or our parents would take our dictation for the story, writing words where there was room. The combination of words and pictures, bound in a stable form, really excited me. I can only describe this feeling as joy.

Decades later, when I started doing comics, that same joy came back, remarkably unpolluted!

My interests were so varied growing up, but they always centered around the study of character. I could have learned any subject well if there were compelling characters involved.

The school system back then was geared toward verbal and pattern-based/logical/verbal thinkers. Kinesthetic and character-based thinkers had to make our own way. I wish that higher math had been taught with characters, since it is so much about relationships and solving for unknowns. These can all be translated into character gestalts, involving emotion and even comedy in a way that makes abstract ideas stick.

I processed and translated experience in terms of character, either taking on the qualities of other people, or assigning characters to abstract ideas or words, such as the days of the week. Character created relevance.

So whether I was studying acting or music history, opera or eventually working in animation, I was always interested in characters and how they interacted and thought. Directing and storyboarding for animation was a very exciting experience, because never before had I the opportunity to see characters I'd drawn come alive in other people's hands! It was fantastic! A great way to connect with great artists. But the strictures of children's TV writing kept the stories from getting deeper, so comics seemed like the next logical step. Comics allowed for that gestalt experience, getting characters and their context to represent philosophical, ethical and emotional states.

RG: You've certainly got some abstract ideas attached to character in Temperance. There is a good balance between characters representing ideas, but also being real people (at least with Minerva and Lester, less so with Pa and Peggy). How did these characters come together in your mind? Did you begin the book with large ideas that you wanted to wrestle with or did you start with characters that these ideas glommed onto?

CM: I started with the idea of war and how it may be the larger expression of our struggle with entropy. Let's face it: nobody is a fan of decay!! Who wants to slide into chaos and emerge transformed? Even though that's the way of things it's too scary to contemplate! We all want to take our minds off this stuff, but it's there in the background. So we have to deal with it consciously or unconsciously. This story is all about entropy and synthesis; the two sides of change, the dual nature of everything. Of these two constants, entropy (and its psychological counterpart oblivion) gets most of our attention, paradoxically because we don't like facing it head-on. Look at our culture now: we hate decay as much we glorify it. Our pervasive way of dealing with it, of beating it to the punch, is violence. We glorify violence because it is entropy under the illusion of our control.

I looked at violence as our sped-up version of entropy, our way of fooling ourselves into overcoming nature. If we can just destroy things, we will somehow live, conquering nature. If we can harness what nature does, we won't have to succumb to it. Tearing things down, blowing them up, gives us the temporary illusion that we stand over and apart from the forces that shape us. War is the most absurd expression of this illusion.

So I wondered: how would I personify not just this force of entropy, but our deeply uneasy feelings about it? How would this force look to us on an emotional and ethical level? We often judge our own decay as cruel and unrelenting. It seems like a form of self-hatred. So I had to make the Pa character not just driven at every moment to do his destructive work, but to hate himself and everything around him. His "job" as this force is to keep going until even he is destroyed. But of course that's impossible, and he knows it, so he's in torment all the time. He can't enjoy the game he's a part of. Still, with his all histrionics he seems impressive and all-powerful.

On the flip side, everything that seems gentle, receptive and creative is still seen as weak in our mass culture. While we judge entropy harshly we often ignore synthesis/creation. This force, which Peggy represents, is very subtle much of the time. Peggy is in the background, in everything. Her influence is practically invisible so it's easy to forget her. She goes about her business more slowly. To personify her would involve a sense of knowing, kindness, compassion and, of course, love. Sadly these qualities still get punished in our popular culture. So Peggy must work "underground," just as the sustaining core of any culture must plan for rebuilding even while the fires rage above.

RG: Yeah, I’m picking up what you are laying down. Why is it that destroyers always trump creators? I guess it’s just much easier to destroy something than to create. I always think about how a given population only needs a small percentage of their number bent on destruction to make the society absolute hell. How many terrorists does it take, or corrupt government officials, or faulty oil rigs? It can seem like a lost cause. Your book ends on a note of hope. Are you completely full of shit?

CM: Destroyers are generally more seductive than creators because bonding via primitive instincts is easy, immediate and addictive. Destruction generally requires less skill and time than creation (even a three-year-old can start a forest fire), so any spectator can say "Hey, I can do that!” Creators, on the other hand, are methodical and patient, representing the more executive functions in the brain. They can seem more intimidating, since they don’t have that immediate bond with our simple instincts. Can you think of many people in our popular culture who are admired for their patience and persistence? False, fast power is always more impressive to more people, especially people who haven’t developed their skills at patience and methodical thinking, or who live primarily in their instinct-based emotions.

Another reason the destructive minority grabs influence is that we are transfixed by our own awe at destruction, at seeing natural forces hijacked in the form of grand spectacle. I have a hunch that our fascination with destruction is an outgrowth of our neurological need for contrasts and patterns. We need to find patterns and disrupt them, to keep our brains awake. And we are fascinated at our own fascination, too. Humans can't seem to get enough of ourselves…

Big disturbances, for good or for ill, really wake us up, sending ripples through the wider cultural mind.

The end of the book is a tableau of a cycle coming around again. Whether or not it’s hopeful is up to the reader!

RG: Since we are on the topic of patience and creating, I wanted to talk to you about comic making. You’ve been making your living in animation and have been drawing storyboards for many years. While there are some skills that translate well into comics, comics still have aspects that do not have any overlap (like designing a page to work as a whole, placing blacks and whites, and a nice, finished drawing). Did you find it difficult to make that transition? Was there anyone you looked at when (or if) you felt a little shaky?

CM: I’m really driven by story and character, and this applies to both media. It’s a pretty intuitive process, waiting to “see” the next scene or panel once I am emotionally involved. As far as page design goes, a lot of my visual instincts come from doing paintings. I don’t paint often, but when I do it’s a quite a challenging exercise of balancing all those things you mentioned. More than producing a nice finished drawing, I want to get into the scene. Once the scene feels “real” the drawing is finished. It’s great looking at other people’s work, and their influence sinks in, but I don’t usually analyze it. Getting too analytical takes all the fun away!

RG: I know what you mean. There is also the phrase, “Paralysis by analysis” that can creep in too. At some point you have to trust your instincts. However, you appear to be blessed in that good artistic decisions seem to come naturally to you, where I need years of studying and practice to put things together.

CM: Well, what may appear to you as good instincts is really the end product of hitting a lot of intellectual and creative brick walls. I always do a mountain of preparation then get frustrated and give up, at least until my brain airs out. At that point all you can do is let go and trust that all the research and notes and sketches will sort themselves out. So however you slice it, we're both putting in years of study and practice. And, by the way, your work just gets more and more stunning.

RG: Now that you have two graphic novels out in 3 years, what’s next? Are you going to do another big book or do you want to try something shorter? Do you have any interest in reprinting some of your short stories?

CM: I am so ready to do a comedy now! And shorter books, too! It'd be good to see what Percy Gloom is up to — he'd be a great little guy to work with again. I also have this novella I wrote that needs some spot drawings and paintings, so that'll be fun, too. There's a mini-comic I did a while back called "Little Miss Mess" about a couple of incognito space aliens. I really like the main characters and wouldn't mind continuing their adventures. So ideas are rolling around in the old noggin. I just need to find out which one is shouting the loudest.